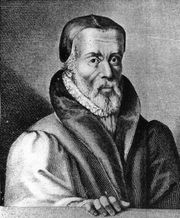

William Tyndale

| William Tyndale | |

|---|---|

Protestant reformer and Bible translator |

|

| Born | c. 1494 Gloucestershire, England |

| Died | 6 October 1536 near Brussels, Belgium |

William Tyndale (sometimes spelled Tindall or Tyndall; pronounced /ˈtɪndəl/) (c. 1494 – 1536) was a 16th century scholar and translator who became a leading figure in Protestant reformism towards the end of his life. He was influenced by the work of Desiderius Erasmus, who made the Greek New Testament available in Europe, and Martin Luther.[1] Tyndale was the first to translate considerable parts of the Bible into English, for a public, lay readership. While a number of partial and complete translations had been made from the seventh century onward, particularly during the 14th century, Tyndale's was the first English translation to draw directly from Hebrew and Greek texts, and the first to take advantage of the new medium of print, which allowed for its wide distribution. This was taken to be a direct challenge to the hegemony of both the Catholic church and the English church and state. Tyndale also wrote, in 1530, The Practyse of Prelates, opposing Henry VIII's divorce on the grounds that it contravened scriptural law.

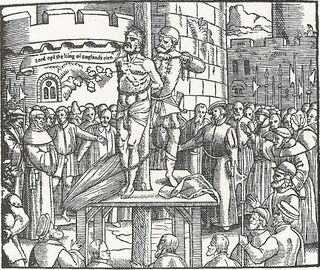

In 1535, Tyndale was arrested by church authorities and jailed in the castle of Vilvoorde outside Brussels for over a year. He was tried for heresy, strangled and burnt at the stake. The heretical Tyndale Bible, as it was known, continued to play a key role in spreading Reformation ideas across Europe.

The fifty-four independent scholars who revised extant English bibles, drew significantly on Tyndale's translations to create the King James Version (or final "Authorised Version") of 1611 (still in mainstream use today). One estimation suggests the King James New Testament is 83.7 % Tyndale's and the Old Testament 75.7 %.[2]

Contents |

Biography

Tyndale was born around 1490, possibly in one of the villages near Dursley, Gloucestershire.[3] Within his immediate family, the Tyndales were also known at that period as Hychyns (Hitchins), and it was as William Hychyns that Tyndale was educated at Magdalen College School, Oxford. Tyndale's family had migrated to Gloucestershire at some point in the fifteenth century - quite probably as a result of the Wars of the Roses. The family derived from Northumberland via East Anglia. Documentation shows that Tyndale's uncle, Edward, was receiver to the lands of Lord Berkeley, and gives account of the Tyndale family origins. Edward Tyndale is recorded in two genealogies[4] as having been the brother of Sir William Tyndale, KB, of Deane, Northumberland, and Hockwald, Norfolk, who was knighted at the marriage of Arthur, Prince of Wales to Katherine of Aragon. Tyndale's family was therefore derived from Baron Adam de Tyndale, a tenant-in-chief of Henry I (and whose family history is related in Tyndall).

Tyndale began a Bachelor of Arts degree at Oxford University in 1512; the same year becoming a subdeacon. He was made Master of Arts in July 1515 and was held to be a man of virtuous disposition, leading an unblemished life.[5] The MA allowed him to start studying theology, but the official course did not include the study of scripture. He was a gifted linguist, over the years becoming fluent in French, Greek, Hebrew, German, Italian, Latin, and Spanish, in addition to his native English.[6] Between 1517 and 1521, he went to the University of Cambridge. Erasmus was the leading teacher of Greek there from August 1511 to January 1514, but during Tyndale's time at the university Erasmus was away.[7] According to Monyahan, Tyndale may have met Thomas Bilney and John Frith whilst there.[8]

Tyndale became chaplain to the house of Sir John Walsh at Little Sodbury and tutor to his children in about 1521. His opinions proved controversial to fellow clergymen, and around 1522 he was called before John Bell, the Chancellor of the Diocese of Worcester, though no formal charges were laid.[9]

Soon afterwards, Tyndale determined to translate the Bible into English, convinced that the way to God was through His word and that scripture should be available even to common people. Foxe describes an argument with a "learned" but "blasphemous" clergyman, who had asserted to Tyndale that, "We had better be without God's laws than the Pope's." Swelling with emotion, Tyndale responded: "I defy the Pope, and all his laws; and if God spares my life, ere many years, I will cause the boy that driveth the plow to know more of the Scriptures than thou dost!" [10][11]

Tyndale left for London in 1523 to seek permission to translate the Bible into English. He requested help from Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall, a well-known classicist who had praised Erasmus after working together with him on a Greek New Testament. The bishop, however, had little regard for Tyndale's scholarly credentials; like many highly-placed churchmen, he was suspicious of Tyndale's theology and was uncomfortable with the idea of the Bible in the vernacular. The Church at this time did not support any English translation of scripture. Tunstall told Tyndale he had no room for him in his household.[12] Tyndale preached and studied "at his book" in London for some time, relying on the help of a cloth merchant, Humphrey Monmouth. He then left England and landed on the continent, perhaps at Hamburg, in the spring of the year 1524, possibly travelling on to Wittenberg. This seems likely given that the name "Guillelmus Daltici ex Anglia“ (a Latin pseudonym for "William Tyndale from England") was entered at that time in the matriculation registers of the University Wittenberg .[13] At this time, possibly in Wittenberg, he began translating the New Testament, completing it in 1525, with assistance from Observant friar William Roy.

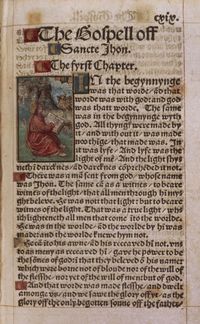

In 1525, publication of the work by Peter Quentell, in Cologne, was interrupted by impact of anti-Lutheranism. It was not until 1526 that a full edition of the New Testament was produced by the printer Peter Schoeffer in Worms, an imperial free city then in the process of adopting Lutheranism.[14] More copies were soon printed in Antwerp. The book was smuggled into England and Scotland, and was condemned in October 1526 by Tunstall, who issued warnings to booksellers and had copies burned in public.[15] Marius notes that the "spectacle of the scriptures being put to the torch" "provoked controversy even amongst the faithful."[15] Cardinal Wolsey condemned Tyndale as a heretic, being first mentioned in open court as a heretic in January 1529.[16]

From an entry in George Spalatin's Diary, on August 11, 1526, it seems that Tyndale remained at Worms about a year. A mystery hangs over the period between his departure from Worms and his final settlement at Antwerp. The colophon to Tyndale's translation of Genesis and the title pages of several pamphlets from this time are purported to have been printed by Hans Luft at Marburg. A clear link is, however, questionable. Hans Luft, the printer of Luther's books, never had a printing-press at Marburg.

Around 1529, it is possible that Tyndale went into hiding in Hamburg, carrying on his work. He revised his New Testament and began translating the Old Testament and writing various treatises. In 1530, he wrote The Practyse of Prelates, opposing Henry VIII's divorce on the grounds that it was unscriptural and was a plot by Cardinal Wolsey to get Henry entangled in the papal courts. The king's wrath was aimed at Tyndale: Henry asked the emperor Charles V to have the writer apprehended and returned to England. Tyndale made his case in An Answer unto Sir Thomas More's Dialogue. In 1532 Thomas More published a six volume Confutation of Tyndale's Answer, in which he alleged Tyndale was a traitor and a heretic.[17][18]

Eventually, Tyndale was betrayed by Henry Phillips to the authorities, seized in Antwerp in 1535 and held in the castle of Vilvoorde near Brussels.[19] He was tried on a charge of heresy in 1536 and condemned to death, despite Thomas Cromwell's intercession on his behalf. Tyndale "was strangled to death while tied at the stake, and then his dead body was burned".[20] Foxe gives 6 October as the date of commemoration (left-hand date column), but gives no date of death (right-hand date column).[19] Tyndale's final words, spoken "at the stake with a fervent zeal, and a loud voice", were reported as "Lord! Open the King of England's eyes."[21] The traditional date of commemoration is 6 October, but records of Tyndale's imprisonment suggest the date might have been some weeks earlier.[22]

Within four years, at the same king's behest, four English translations of the Bible were published in England,[23] including Henry's official Great Bible. All were based on Tyndale's work.

Printed works

Most well known for his translation of the Bible, Tyndale was an active writer and translator. Not only did Tyndale's works focus on the way in which religion should be carried out, but were also greatly keyed towards the political arena.

"They have ordained that no man shall look on the Scripture, until he be noselled in heathen learning eight or nine years and armed with false principles, with which he is an clean shut out of the understanding of the Scripture."

| Year Printed | Name of Work | Place of Publication | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1525 | The New Testament Translation (incomplete) | Cologne | |

| 1526* | The New Testament Translation (first full printed edition in English) | Worms | |

| 1526 | A compendious introduccion, prologue or preface into the epistle of Paul to the Romans | ||

| 1528 | The parable of the wicked mammon | Antwerp | |

| 1528 | The Obedience of a Christen Man[24] (and how Christen rulers ought to govern...) | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1530* | The five books of Moses [the Pentateuch] Translation (each book with individual title page) | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1530 | The practyse of prelates | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1531 | The exposition of the fyrste epistle of seynt Jhon with a prologge before it | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1531? | The prophete Jonas Translation | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1531 | An answere vnto sir Thomas Mores dialogue | ||

| 1533? | An exposicion vppon the. v. vi. vii. chapters of Mathew | ||

| 1533 | Erasmus: Enchiridion militis Christiani Translation | ||

| 1534 | The New Testament Translation (thoroughly revised, with a second foreword against George Joye's unauthorized changes in an edition of Tyndale's New Testament published earlier in the same year) | Antwerp | Merten de Keyser |

| 1535 | The testament of master Wylliam Tracie esquier, expounded both by W. Tindall and J. Frith | ||

| 1536? | A path way into the holy scripture | ||

| 1537 | The bible, which is all the holy scripture Translation (only in part Tyndale's) | ||

| 1548? | A briefe declaration of the sacraments | ||

| 1573 | The whole workes of W. Tyndall, John Frith, and Doct. Barnes, edited by John Foxe | ||

| 1848* | Doctrinal Treatises and Introductions to Different Portions of the Holy Scriptures | ||

| 1849* | Expositions and Notes on Sundry Portions of the Holy Scriptures Together with the Practice of Prelates | ||

| 1850* | An Answer to Sir Thomas More's Dialogue, The Supper of the Lord after the True Meaning of John VI. and I Cor. XI., and William Tracy's Testament Expounded | ||

| 1964* | The Work of William Tyndale | ||

| 1989** | Tyndale's New Testament | ||

| 1992** | Tyndale's Old Testament | ||

| Forthcoming | The Independent Works of William Tyndale | ||

| * | These works were printed more than once, usually signifying a revision or reprint. However the 1525 edition was printed as an incomplete quarto and was then reprinted in 1526 as a complete octavo. | ||

| ** | These works were reprints of Tyndale's earlier translations revised for modern-spelling. |

Legacy

In translating the Bible, Tyndale introduced new words into the English language, and many were subsequently used in the King James Bible:

- Jehovah (from a transliterated Hebrew construction in the Old Testament; composed from the Tetragrammaton YHWH.

- Passover (as the name for the Jewish holiday, Pesach or Pesah),

- Atonement which goes beyond mere "reconciliation" to mean "to unite" or "to cover", which springs from the Hebrew kippur, the Old Testament version of kippur being the covering of doorposts with blood, or "Day of Atonement".

- scapegoat (the goat that bears the sins and iniquities of the people in Leviticus, Chapter 16)

He also coined such familiar phrases as:

- lead us not into temptation but deliver us from evil

- knock and it shall be opened unto you

- twinkling of an eye

- a moment in time

- fashion not yourselves to the world

- seek and you shall find

- ask and it shall be given you

- judge not that you not be judged

- the word of God which liveth and lasteth forever

- let there be light

- the powers that be

- my brother's keeper

- the salt of the earth

- a law unto themselves

- filthy lucre

- it came to pass

- gave up the ghost

- the signs of the times

- the spirit is willing

- live and move and have our being

- fight the good fight

Some of the new words and phrases introduced by Tyndale did not sit well with the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church, using words like 'Overseer' rather than 'Bishop' and 'Elder' rather than 'Priest', and (very controversially), 'congregation' rather than 'Church' and 'love' rather than 'charity'. Tyndale contended (citing Erasmus) that the Greek New Testament did not support the traditional Roman Catholic readings.

Contention from Roman Catholics came not only from real or perceived errors in translation but a fear of the erosion of their social power if Christians could read the bible in their own language. "The Pope's dogma is bloody", Tyndale wrote in his Obedience of a Christian Man.[25] Tyndale translated "Church" as "congregation" and translated "priest" as "elder."[26] Moynahan explains Tyndale's reasons: "This was a direct threat to the Church's ancient- but so Tyndale here made clear, non-scriptural- claim to be the body of Christ on earth. To change these words was to strip the Church hierarchy of its pretensions to be Christ's terrestrial representative, and to award this honour to individual worshipers who made up each congregation."[26] Thomas More commented that searching for errors in the Tyndale Bible was similar to searching for water in the sea, and charged Tyndale's translation of Obedience of a Christian Man with having about a thousand falsely translated errors. Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall of London declared that there were upwards of 2,000 errors in Tyndale's Bible. Tunstall in 1523 had denied Tyndale the permission required under the Constitutions of Oxford (1409), that were still in force, to translate the Bible into English.

In response to allegations of inaccuracies in his translation in the New Testament, Tyndale in the Prologue of his 1525 translation wrote that he never intentionally altered or misrepresented any of the Bible in his translation, but that he has sought to "interpret the sense of the scripture and the meaning of the spirit."[26]

While translating, Tyndale followed Erasmus' (1522) Greek edition of the New Testament. In his Preface to his 1534 New Testament ("WT unto the Reader") he not only goes into some detail about the Greek tenses but also points out that there is often a Hebrew idiom underlying the Greek. The Tyndale Society adduces much further evidence to show that his translations were made directly from the original Hebrew and Greek sources he had at his disposal. For example, the Prolegomena in Mombert's William Tyndale's Five Books of Moses show that Tyndale's Pentateuch is a translation of the Hebrew original. His translation also drew on Latin Vulgate and Luther's 1521 September Testament.[26]

Of the first (1526) edition of Tyndale's New Testament, only three copies survive. The only complete copy is part of the Bible Collection of Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart. The copy of the British Library is almost complete, lacking only the title page and list of contents. Another rarity of Tyndale's is the Pentateuch of which only nine remain.

Impact on the English Bible

| The Bible in English |

| Old English (pre-1066) |

| Middle English (1066-1500) |

| Early Modern English (1500-1800) |

| Modern Christian (1800-) |

| Modern Jewish (1853-) |

| Miscellaneous |

The translators of the Revised Standard Version in the 1940s noted that Tyndale's translation inspired the great translations to follow, including the Great Bible of 1539, the Geneva Bible of 1560, the Bishops' Bible of 1568, the Douay-Rheims Bible of 1582–1609, and the King James Version of 1611, of which the RSV translators noted: "It [the KJV] kept felicitous phrases and apt expressions, from whatever source, which had stood the test of public usage. It owed most, especially in the New Testament, to Tyndale". Many scholars today believe that such is the case. Moynahan writes: "A complete analysis of the Authorised Version, known down the generations as "the AV" or "the King James" was made in 1998. It shows that Tyndale's words account for 84% of the New Testament and for 75.8% of the Old Testament books that he translated.[27] Joan Bridgman makes the comment in the Contemporary Review that, "He [Tyndale] is the mainly unrecognised translator of the most influential book in the world. Although the Authorised King James Version is ostensibly the production of a learned committee of churchmen, it is mostly cribbed from Tyndale with some reworking of his translation."

Many of the great English versions since then have drawn inspiration from Tyndale, such as the Revised Standard Version, the New American Standard Bible, and the English Standard Version. Even the paraphrases like the Living Bible have been inspired by the same desire to make the Bible understandable to Tyndale's proverbial ploughboy.[28][29]

George Steiner in his book on translation After Babel refers to "the influence of the genius of Tyndale, the greatest of English Bible translators..." [After Babel p. 366]

Memorials

A memorial to Tyndale stands in Vilvoorde, where he was executed. It was erected in 1913 by Friends of the Trinitarian Bible Society of London and the Belgian Bible Society[30] There is also a small William Tyndale Museum in the town, attached to the Protestant church.[31]

A bronze statue by Sir Joseph Boehm commemorating the life and work of Tyndale was erected in Victoria Embankment Gardens on the Thames Embankment, London in 1884. It shows his right hand on an open Bible, which is itself resting on an early printing press.

The Tyndale Monument was built in 1866 on a hill above his supposed birthplace, North Nibley, Gloucestershire.

A number of colleges, schools and study centres have been named in his honour, including Tyndale House (Cambridge), Tyndale University College and Seminary (Toronto), the Tyndale-Carey Graduate School affiliated to the Bible College of New Zealand, William Tyndale College (Farmington Hills, Michigan), and Tyndale Theological Seminary (Shreveport, Louisiana, and Fort Worth, Texas), as well as the independent Tyndale Theological Seminary [32] in Badhoevedorp, near Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

An American Christian publishing house, also called Tyndale House, was named after Tyndale.

Liturgical commemoration

By tradition Tyndale's death is commemorated on 6 October.[33] There are commemorations on this date in the church calendars of members of the Anglican Communion, initially as one of the "days of optional devotion" in the American Book of Common Prayer (1979)[34], and a "black-letter day" in the Church of England's Alternative Service Book[35]. The Common Worship that came into use in the Church of England in 2000 provides a collect proper to 6 October, beginning with the words:

"Lord, give your people grace to hear and keep your word that, after the example of your servant William Tyndale, we may not only profess your gospel but also be ready to suffer and die for it, to the honour of your name; …"

See the List of Anglican Church Calendars.

Tyndale is also honored in the Calendar of Saints of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America as a translator and martyr the same day.

Films about William Tyndale

In 1937 the first film about the life of William Tindale was made.[36] The second film God's Outlaw: The Story of William Tyndale[37] was released in 1986. A cartoon film about his life with the title Torchlighters: The William Tyndale Story was released ca. 2005. In the Film Stephen's Test of Faith (1998) is a long scene with William Tyndale, how he translated the bible and how he is put to death.[38]

Ca. 2006 was a documentary film William Tyndale: Man with a Mission published. This documentary included an interview with Daniell, David. Another known documentary is the film William Tyndale: His Life, His Legacy.

See also

- Tyndale Bible

- Luther Bible

- Matthew Bible

- King James Bible

- English translations of the Bible

- Tyndale House

Notes

- ↑ Scientifically proven, see: Tyndale, William (tr.); Martin, Priscilla (ed.) (2002); p. xvi and see also: Daniell, David (1994) William Tyndale: a biography. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, p. 114, line 33 and see also: Vogel, Gudrun (2009) "Tyndale, William" in: Der Brockhaus in sechs Bänden. Mannheim/Leipzig: Brockhaus Verlag and see also: Zwahr. A. (2004) Tyndale, William" in: Meyers Großes Taschenwörterbuch. Mannheim: Bibliographisches Institut

- ↑ How Much of the King James Bible is William Tyndale's - abstract of John Nielson and Royal Skousen text, in: REFORMATION - Volume Three.(1998)

- ↑ His date of birth is unclear, with sources giving dates varying between 1484 and 1496.

- ↑ John Nichol, Literary Anecdotes, Vol IX: Tindal genealogy; Burke's Landed Gentry, 19th century editions, 'Tyndale of Haling'

- ↑ Brian Moynahan. William Tyndale. If God Spare my Life. Abacus. London. 2003. p11.

- ↑ eg Daniell, David (1994) William Tyndale: a biography. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, p. 18

- ↑ eg Daniell, David (1994) William Tyndale: a biography. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, p. 49-50

- ↑ Brian Moynahan. William Tyndale. If God Spare my Life. Abacus. London. 2003. p21.

- ↑ Brian Moynahan. William Tyndale. If God Spare my Life. Abacus. London. 2003. p28

- ↑ Lecture by Dom Henry Wansbrough OSB MA (Oxon) STL LSS

- ↑ Foxe's Book of Martyrs, Chap XII

- ↑ Tyndale, preface to Five bokes of Moses (1530).

- ↑ eg The Life of William Tyndale – Tyndale in Germany – by Dr. Herbert Samworth

- ↑ Joannes Cochlaeus, Commentaria de Actis et Scriptis Martini Lutheri (St Victor, near Mainz: Franciscus Berthem, 1549), p. 134.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Peter Ackroyd. The Life of Thomas More. Vintage, London 1999. p270.

- ↑ Brian Moynahan. William Tyndale. If God Spare my Life. Abacus. London. 2003. p177

- ↑ Brian Moynahan. William Tyndale. If God Spare my Life. Abacus, London ISBN 034911532 p248.

- ↑ Moynahan means that More "despised, feared and loathed Tyndale; he, and his English Testament, were the obsessions of More's life. His hatred was not slaked by the savaging he had given Tyndale in his Dialogue, nor by the half a million words he had poured into the Confutation, this was mere flood of ink, where More was satisfied only by blood and the flames of the 'shorte fyre." Monynahan makes the case that More was a powerful factor in the betrayal and death of Tyndale. Compare. Brian Moynahan. William Tyndale. If God Spare my Life. Abacus, London ISBN 034911532 p340.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 John Foxe, Actes and Monuments (1570), VIII.1228 (Foxe's Book of Martyrs Variorum Edition Online).

- ↑ Michael Farris, "From Tyndale to Madison", 2007, p. 37.

- ↑ John Foxe, Actes and Monuments (1570), VIII.1229 (Foxe's Book of Martyrs Variorum Edition Online).

- ↑ Arblaster, Paul (2002). "An Error of Dates?". http://www.tyndale.org/TSJ/25/arblaster.html. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ↑ Miles Coverdale's, Thomas Matthew's, Richard Taverner's, and the Great Bible

- ↑ The Obedience Of A Christian Man

- ↑ Brian Moynahan. William Tyndale. If God Spare my Life. Abacus, London ISBN 034911532 p152.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Brian Moynahan. William Tyndale. If God Spare my Life. Abacus, London ISBN 034911532 p72

- ↑ Brian Moynahan. William Tyndale. If God Spare My Life. Abacus, London. 2003 pp1-2.

- ↑ The Bible in the Renaissance - William Tyndale

- ↑ http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Book_of_Martyrs/Chapter_XII

- ↑ Le Chrétien Belge, October 18, 1913; November 15, 1913.

- ↑ museum.com

- ↑ Tyndale Theological Seminary

- ↑ David Daniell, “Tyndale, William (c.1494–1536),” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison (Oxford: OUP, 2004); online edition, ed. Lawrence Goldman, October 2007. Accessed December 18, 2007.

- ↑ Marion J. Hatchett, Commentary on the American Prayer Book (New York: Seabury press, 1981), pp. 43, 76-77

- ↑ Martin Draper, ed., The Cloud of Witnesses: A Companion to the Lesser Festivals and Holydays of the Alternative Service Book, 1980 (London: The Alcuin Club, 1982).

- ↑ compare William Tindale (1937)

- ↑ compare God's Outlaw: The Story of William Tyndale

- ↑ compare Stephen's Test of Faith (1998)

Further references

- Adapted from J.I. Mombert, "Tyndale, William," in Philip Schaff, Johann Jakob Herzog, et al., eds., The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1904, reprinted online by the Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Additional references are available there.

- David Daniell, William Tyndale, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- William Tyndale, The New Testament, (Worms, 1526; Reprinted in original spelling and pagination by The British Library, 2000 ISBN 07123-4664-3)

- William Tyndale, The New Testament, (Antwerp, 1534; Reprinted in modern English spelling, complete with Prologues to the books and marginal notes, with the original Greek paragraphs, by Yale University Press, 1989 ISBN 0-300-04419-4)

- This article includes content derived from the Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, 1914, which is in the public domain.

- Paul Arblaster, Gergely Juhász, Guido Latré (eds) Tyndale's Testament hardback ISBN 2-503-51411-1 Brepols 2002

- Day, John T. "Sixteenth-Century British Nondramatic Writers" Dictionary of Literary Biography 1.132 1993 :296-311

- Foxe, Acts and Monuments

- Cahill, Elizabeth Kirkl "A bible for the plowboy", Commonweal 124.7: 1997

- The Norton Anthology: English Literature. Ed. Julia Reidhead. New York: New York, Eighth Edition, 2006. 621.

- Brian Moynahan, God's Bestseller: William Tyndale, Thomas More, and the Writing of the English Bible---A Story of Martyrdom and Betrayal St. Martin's Press, 2003

- John Piper, Desiring God Ministries, "Why William Tyndale Lived and Died" [1]

- William Tyndale: A hero for the information age," The Economist, 2008 December 20, pp. 101-103. [2] The online version corrects the name of Tyndale's Antwerp landlord as "Thomas Pointz" vice the "Henry Pointz" indicated in the print edition.

- Ralph S. Werrell, "The Theology of William Tyndale." ISBN 0 227 67985 7. With a Foreword by Dr. Rowan Williams. Published by James Clarke & Co.